Critical thinking is one of the most important tools you can have in your arsenal of tactics to beat your opponents, whether it is your woke college professor, your leftist co-workers, or a friendly banter with peers.

Knowing how to pick apart arguments and the mistakes in them will be invaluable.

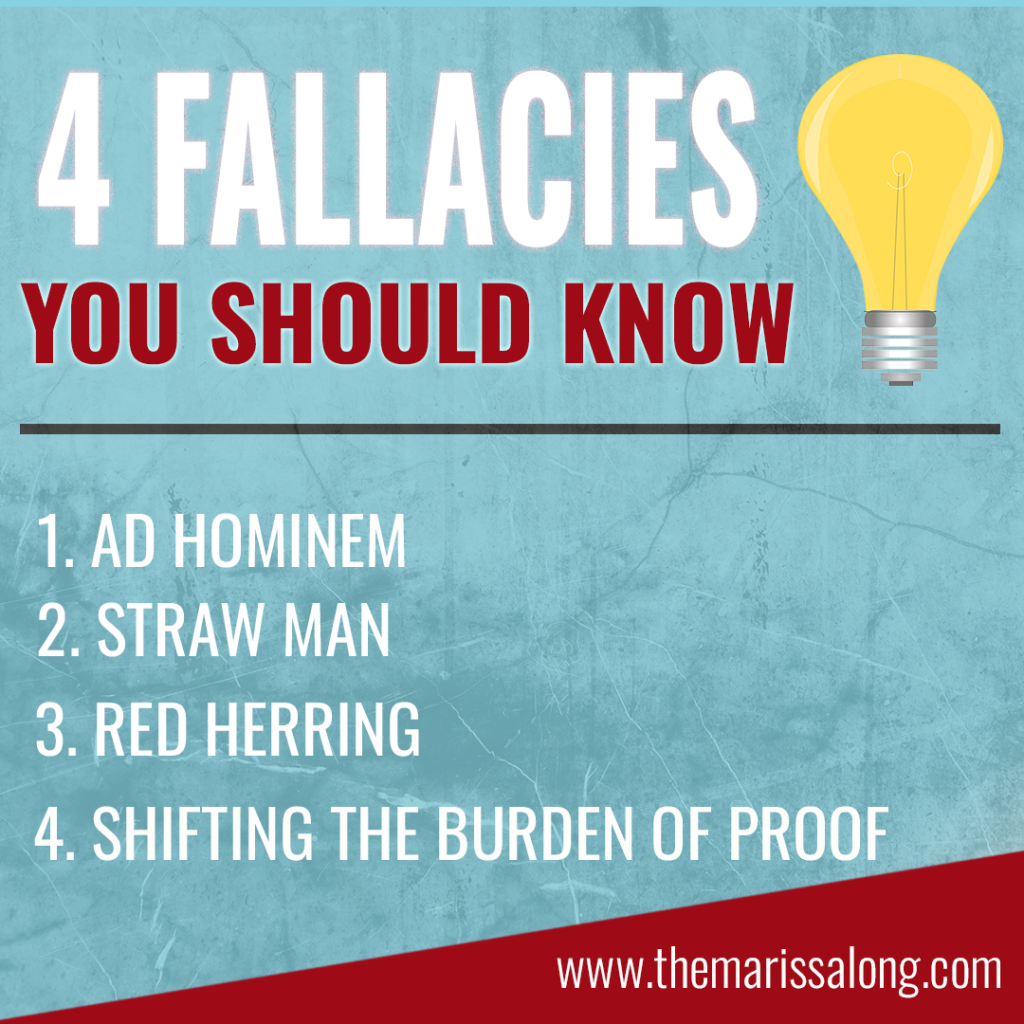

Meet four types of fallacies you should know: ad hominem, the straw man, red herring, and shifting the burden of proof!

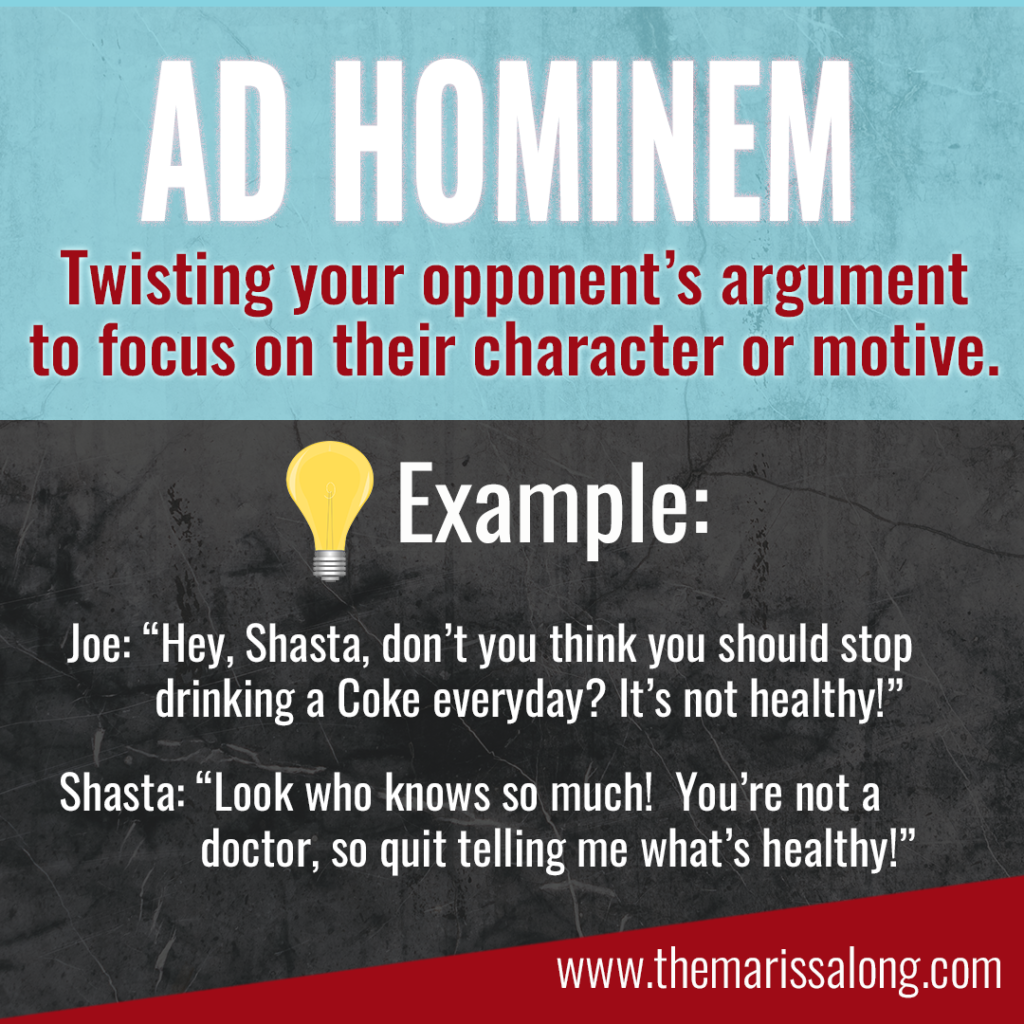

1. Ad Hominem

We’re gettin’ techy here! Ad hominem is Latin for “to the man” and involves distracting opponents.

Ad hominem takes several forms but is essentially twisting an argument so that when your opponent makes an argument, you turn around and focus on his or her personal flaws or motive, rather than the argument they made. This gets you out of the process of arguing your position and puts them in a position of defending their character or whatever flaw you chose to focus on.

Ad hominem fallacies are “based on attacks against the person making an argument instead of criticizing the argument itself.”

Example:

Joe: “Hey Shasta, you might want to stop drinking a Coke everyday. The sugar’s not good for your health.”

Shasta: “Well, look who knows so much! You’re not a doctor, so quit telling me how to take care of my health!”

Shasta took the focus right off Joe’s argument that Coke is unhealthy and is now forcing him to defend himself.

Ad hominem is especially popular in politics and is called “mudslinging”. Ad hominem can also take other forms, including abusive ad hominem and circumstantial ad hominem.

A. Abusive Ad Hominem

An abusive ad hominem attacks the character of an opponent. Again, this is often seen in politics, especially in name-calling.

B. Circumstantial Ad Hominem

A circumstantial ad hominem occurs “when a critic simply dismisses a person’s argument based on the arguer’s circumstances.” For example, if you work for a fertilizer company and you say the government should reduce its regulations on fertilizer, your friend could use circumstantial ad hominem to point out that your job with a fertilizer company gives you a bias in your opinion on fertilizer regulations.

Sometimes circumstantial ad hominem arguments are warranted, but other times, they become a fallacy that distracts from the real issue.

<<Also Read Attacking Religious Freedom is a Direct Attack On Freedom of Thought!

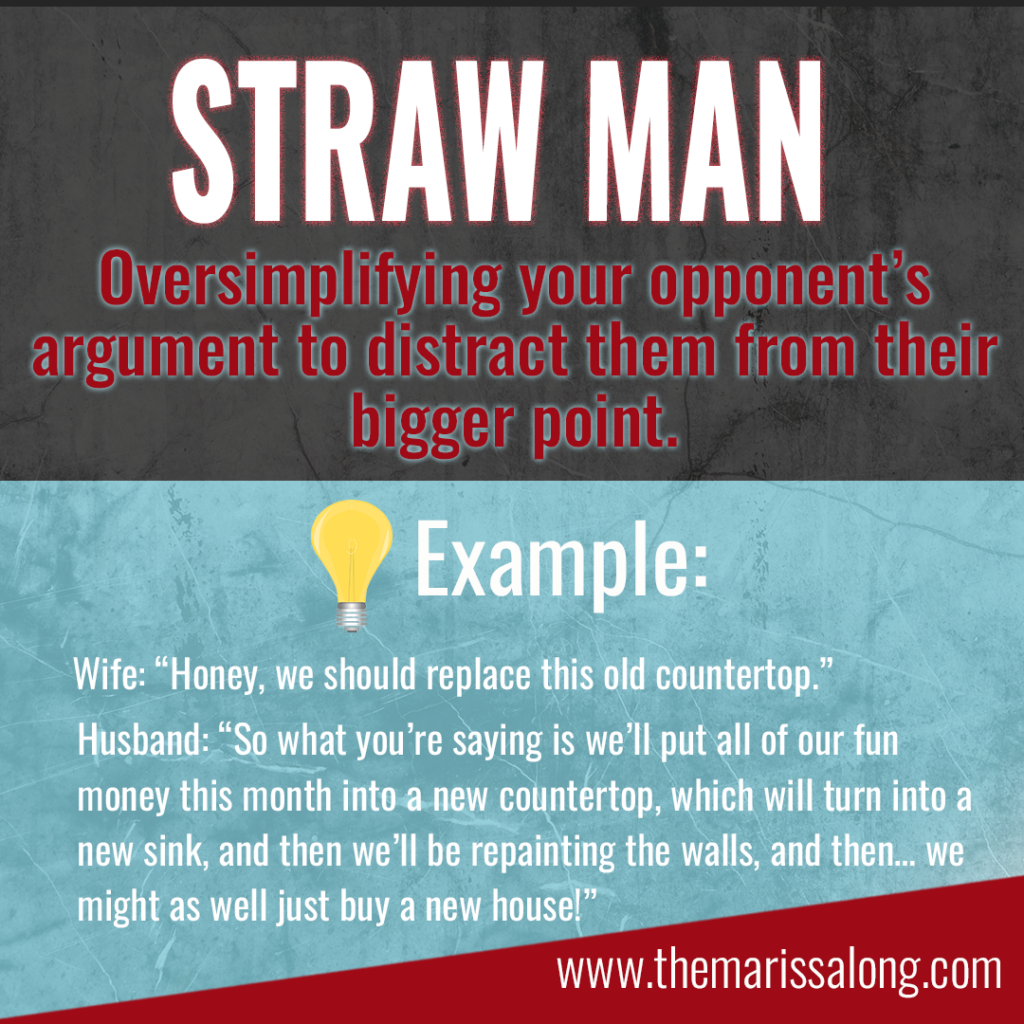

2. Straw Man

The Straw Man fallacy occurs when you oversimplify your opponents’ argument to distract them from their bigger point. It’s like a scare crow or “straw man” in a farmer’s field. It distracts (or scares) the crows away from the corn in the field so they don’t eat the farmer’s crop.

Example:

Sally (talking to her husband): “Honey, I think we should replace this countertop. The finish is flaking off.”

Josh: “So what you’re saying is we’ll put all of our fun money this month into a new countertop, which will turn into a new sink, and then before you know it, we’ll be repainting the walls, and then… we might as well just buy a new house. I’m NOT installing a new countertop!”

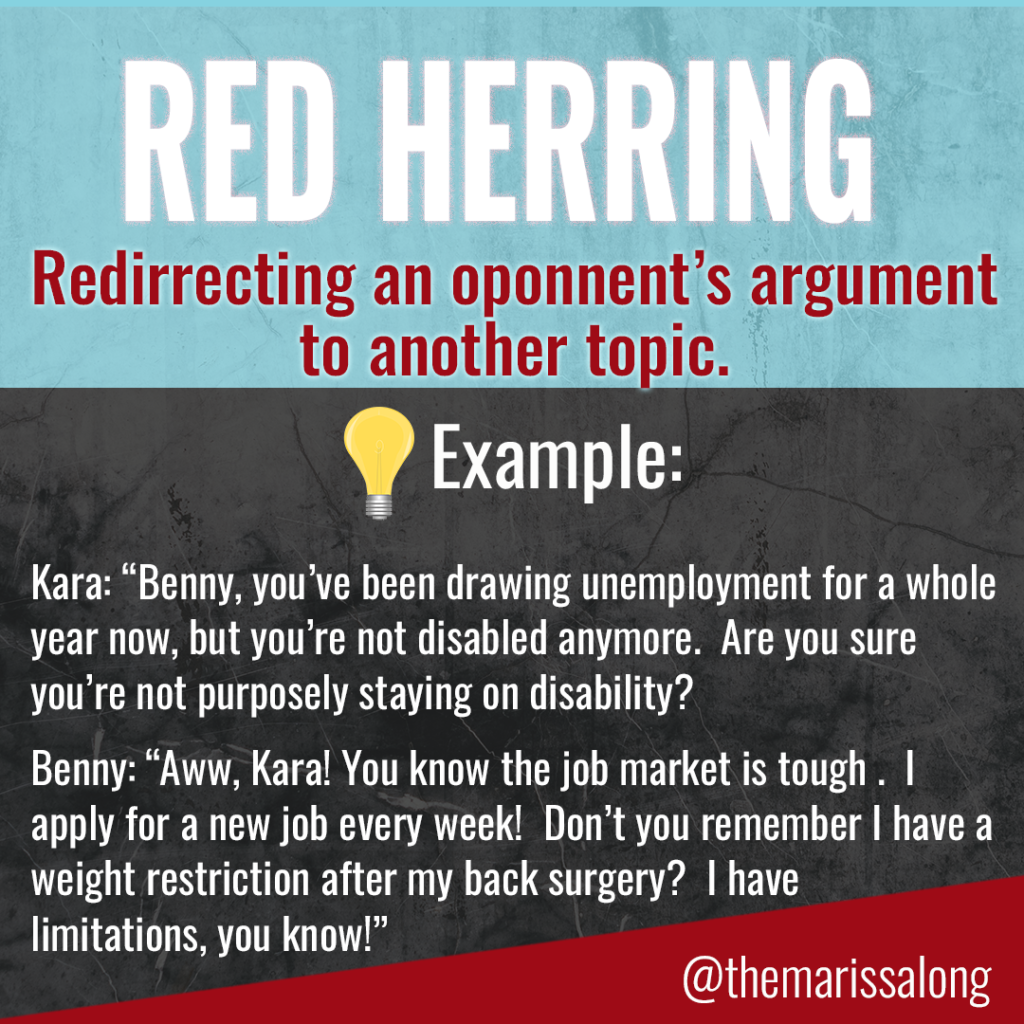

3. Red Herring

Red herring is my favorite logical fallacy because… well… it’s easy to remember. Ha!

The red herring is essentially a distraction from the original argument that an opponent makes. It sounds like the ad hominem, but it’s a little different.

“In rhetoric and argumentation, it’s a fallacy that is committed when someone deliberately tries to derail a discussion from the issue at hand to a new, unrelated topic” (Fallacy In Logic).

The red herring switches topics, whereas the ad hominem points the argument back on the character or experience of the opponent. The red herring is often used to avoid an uncomfortable question.

Example:

Kara: “Benny, you’ve been drawing unemployment for a whole year now, and you’re not disabled anymore. I think you’re just applying for jobs to keep your unemployment status for government welfare.”

Benny: “Aww, Kara, come on now! You know the job market is tough right now. I apply for a new job every week! Don’t you remember I have a limit on how much I can lift after my back surgery? My job selection is limited!”

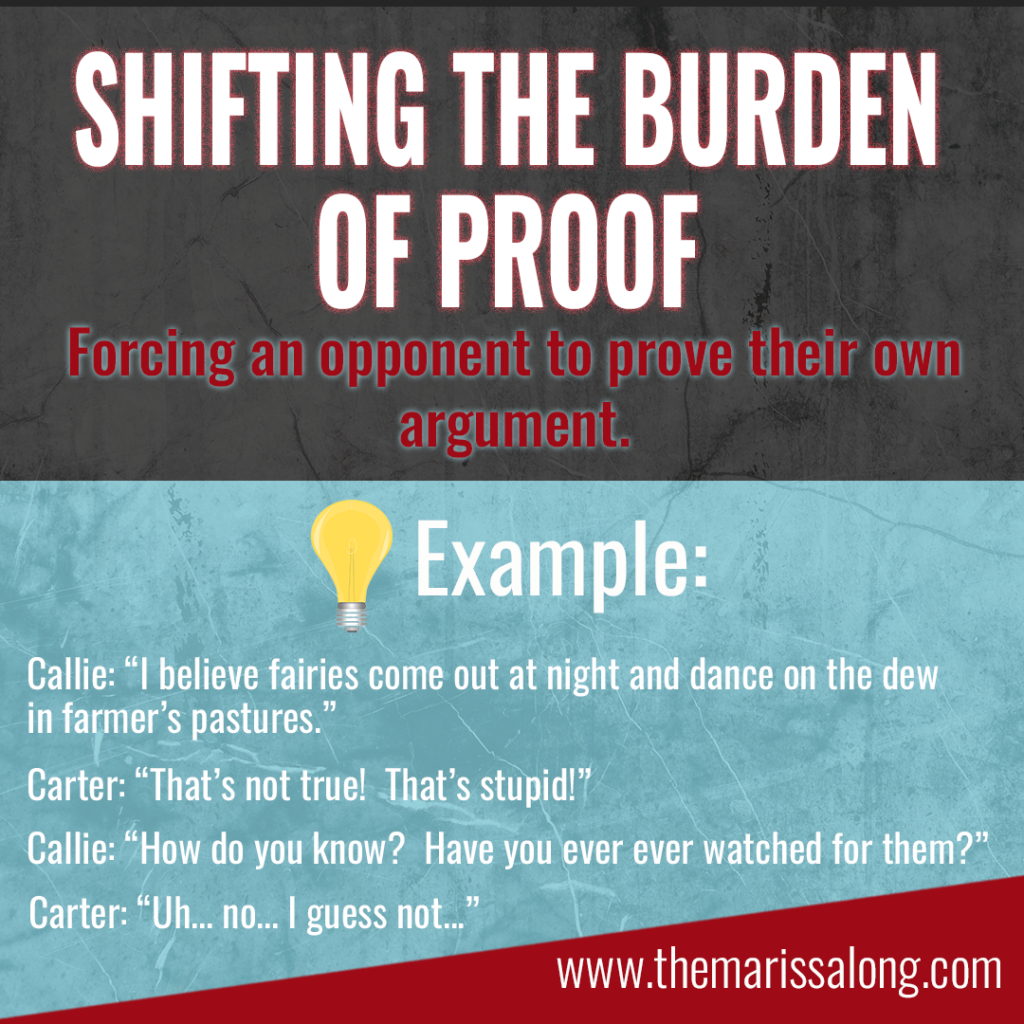

4. Shifting the Burden of Proof

When someone makes an argument, they have the “burden of proof” to prove that their argument is valid.

When someone shifts the burden of proof, a fallacy can often occur. The burden of proof fallacy is often used in religious arguments, but it can be used in other areas as well.

Example:

Callie: “I believe fairies come out at night and dance on the dew in farmer’s pastures.”

Carter: “How do you know that?”

Callie: “Well, can you disprove it? Have you ever looked?”

Carter: “Uh…no… I guess not…”

Conclusion

Put the definitions of these logical fallacies in your arsenal of debating weapons, and call your professors, co-workers, and classmates out when they use them. If done respectfully, the knowledge of these fallacies can spark some fascinating conversations and uncover hidden personal biases on both parties!

One comment