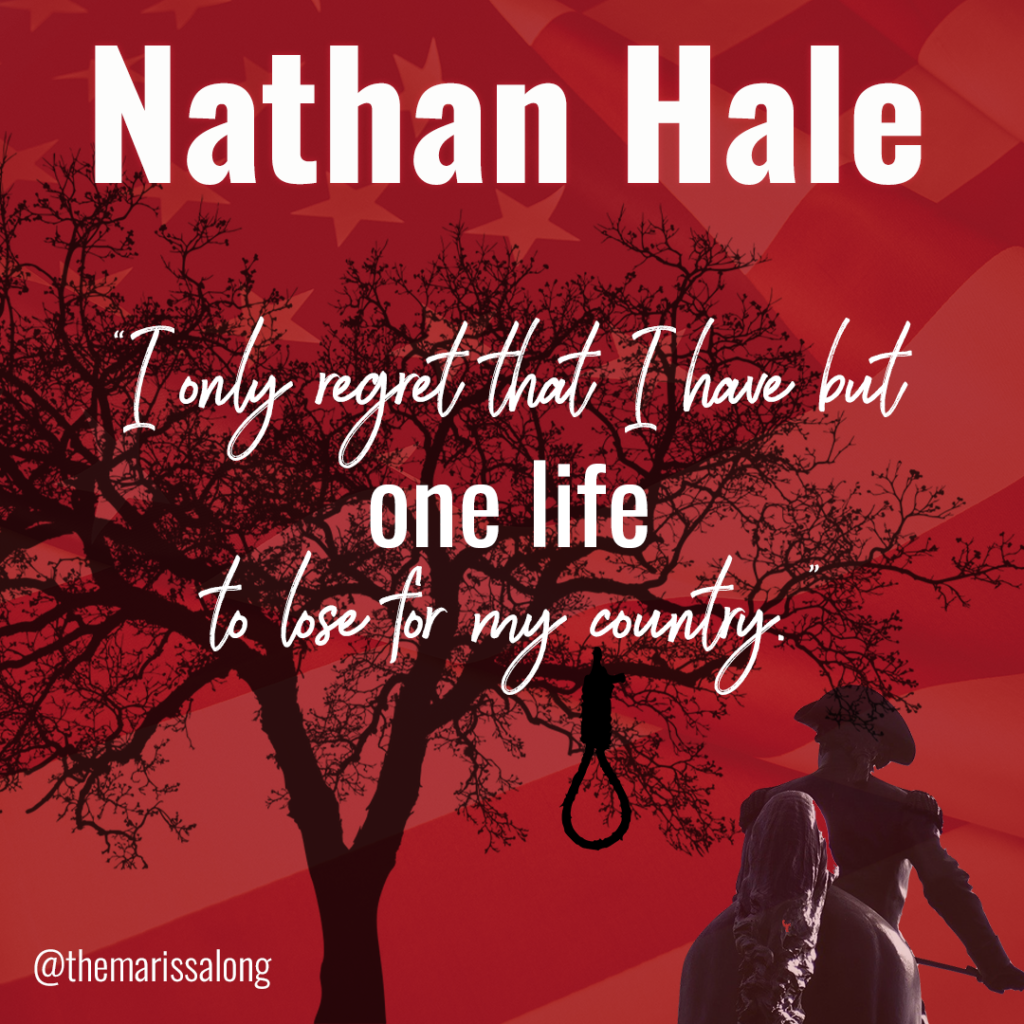

On September 22 1776, a 21-year-old American was hanged for spying on the British in the service of the American Revolution. His name was Nathan Hale, and he is renowned for the words, “I only regret that I have but one life to lose for my country.”

These words inspired thousands of other American colonists to rise up and unite as one force to throw off the oppressive ruling of Britain and establish one of the greatest experiments of the world: the United States of America.

Nathan Hale as a Boy

Nathan Hale was born in Coventry, Connecticut on June 6, 1755. His parents were Richard Hale and Elizabeth Strong Hale. His family were Puritans and well-to-do farmers, and he worked on the farm until he was 13 and attended Yale with his older brother.

Hale thrived in the academic sphere as he joined the literary fraternity, Linonia, to study cultural topics (slavery included) and science, mathematics, and literature. He also met Benjamin Tallmadge, with whom he became good friends and would continue until his tragic death.

He graduated with honors in 1773 at the age of 18 and became a schoolteacher in East Haddam and later in New London. He offered classes for young women and was an outspoken critic of gender inequality in the educational system of that time. His schoolteacher career was cut short when the American Revolution began with the battles of Lexington and Concord in 1775.

Joining Up: Captain Hale

Nathan Hale followed in the footsteps of his two older brothers and joined the Connecticut militia on July 6, 1775. He spoke at community meetings in favor of military action but didn’t get his chance to see active duty until 1776. Benjamin Tallmadge, his former classmate, wrote Hale a letter on July 4, 1775 urging Hale to join active duty. Tallmadge was General Washington’s aide-de-camp and would go on to become Washington’s director of military intelligence in 1778. After this correspondence with Tallmadge, Hale took his friend’s advice and was commissioned as a first lieutenant.

This commission launched Hale’s legendary military career, as he was stationed in New London and then sent to Cambridge where, on September 14, 1775, his regiment became part of the left wing of General George Washington’s army. His regiment played a key part in commanding “the route from Charleston, which was one of only two roads the British could use to exit Boston” (Totally History). In January 1776, Hale and his regiment were transferred to the right wing in Roxbury and fought to drive the British out of Boston, with much success (Totally History).

In January 1776, Hale was promoted to Captain under General Charles Webb in the 7th Connecticut Regiment.

America’s Spy

As spring broke in 1776, Hale’s regiment came under the personal command of General Washington in Manhattan, guarding the British from invading and controlling New York. Washington knew the British were planning an invasion, but he didn’t know when, where, and how. He needed a volunteer, and Hale stepped up to the task. His decision was made on September 8, 1776.

Hale chose the disguise of a Dutch schoolteacher and crossed enemy lines on September 12, 1776. Just three days later, on September 15, the British successfully invaded New York, and Washington’s forces were pushed back to Manhattan Island’s north end. Hale stayed where he was in British territory.

Captured

The Great New York Fire of 1776 destroyed a large portion of lower Manhattan on September 21, and it sparked the arrest of approximately 200 American partisans. This was Hale’s demise, and the British captured him in Flushing Bay near Queens, New York and taken to British headquarters (New York).

Past this point, accounts are sketchy and differ as to what really happened. Nancy Finley from the Connectitcut History website, states, ““He left his uniform, commission, and official papers behind in Norwalk, and, dressed as a schoolmaster in a plain brown suit and a round hat… He should have made a convincing schoolmaster since he taught school for two years before joining the army, but he asked too many questions and soon aroused suspicion.”

Others say that Samuel Hale, a cousin of the Hales, spotted Hale and turned him in to the British. Still another account says that Major Robert Rogers who was an officer of the Queen’s Rangers tricked Hale at a tavern.

Accounts state that Hale was interrogated by British General William Howe, and the British discovered incriminating evidence in papers Hale had hidden in his shoes. These papers included information about British fortifications, positions, enemy troop numbers and other information that would have benefited Washington’s forces.

A Patriot Executed For Serving His Country

On the morning of September 22, 1776, Hale was executed by the British without a trial, as was the custom of wartime standards at that time. The tragic but patriotic death of one of America’s most legendary spies occurred near a tavern that is near the corner of what is now Third Avenue and 66th Street. Before his death, the 21-year-old patriot was denied a Bible or a clergyman’s presence, even after he requested it. It is also thought that he wrote two letters, but they were destroyed after he was hanged.

Many historical sources state that he gave a patriotic speech before his death, and the words, “I only regret that I have but one life to give for my country” became legendary. Whether factual or not, they inspired thousands of other Americans, many of whom served as spies for General Washington.

General Howe ordered his men to leave Hale’s body hanging from the tree for a few days as an ominous reminder to future would-be spies from Washington’s Continental Army. Hale’s grave was unmarked.

Nathan Hale the Legend

History indicates that Hale was not a good spy, but his patriotism and bravery followed him throughout history’s pages. His sacrifice was one of countless American deaths in the fight for America’s freedom, and it is an unforgettable piece of the legacy that we live in today as the United States of America.

Who is your favorite American hero? Let me know in the comments below!

2 comments